Continuing with cash management publications, this article exemplifies how matching the duration of financial investments with their uses allows Apple to maximize returns without the need to invest in higher-risk instruments.

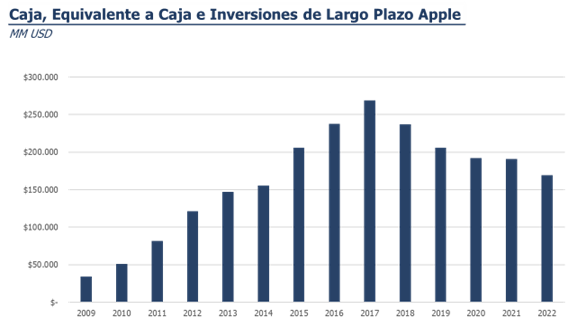

Why did Apple accumulate over $200 billion in cash? It’s not just because its cash inflows exceed outflows, but also due to a carefully planned tax structure aimed at minimizing tax payments. This structure allows Apple to retain nearly 70% of its annual profits in tax havens, such as Ireland, Bermuda, and more recently, Jersey, where the company is virtually exempt from paying taxes. However, this tax savings strategy has made it impossible for Apple to repatriate profits to the U.S., as doing so would incur a 35% corporate tax imposed by the U.S. government on company earnings. For now, the company has preferred to take on debt rather than repatriate its profits.

Much has been said that Apple is the world’s largest high-risk hedge fund, but that’s not quite the case. In 2006, Apple created a subsidiary in the state of Nevada (a state that doesn’t levy corporate taxes and doesn’t require investment firms to disclose their portfolio details) with fewer than 10 employees called Braeburn Capital, mandated to manage Apple’s available cash, particularly the cash held outside the U.S. that Apple does not want to repatriate due to corporate tax obligations.

The amounts managed by Braeburn have exceeded $244 billion, equivalent to Chile’s GDP in 2020. With this enormous cash reserve, the temptation to include higher-risk instruments (such as derivatives or high-yield bonds) in the portfolio to seek higher returns and outperform market benchmarks is immense. However, to the surprise of many, Apple defined the same cash management principles that we find in companies in Chile and around the world, which we discussed in the previous post: capital preservation and liquidity assurance before returns. These principles have been complemented by a strict investment policy that limits investments to instruments from highly-rated issuers (such as government bonds from developed countries and “investment-grade” corporate bonds) and limits exposure to any single issuer.

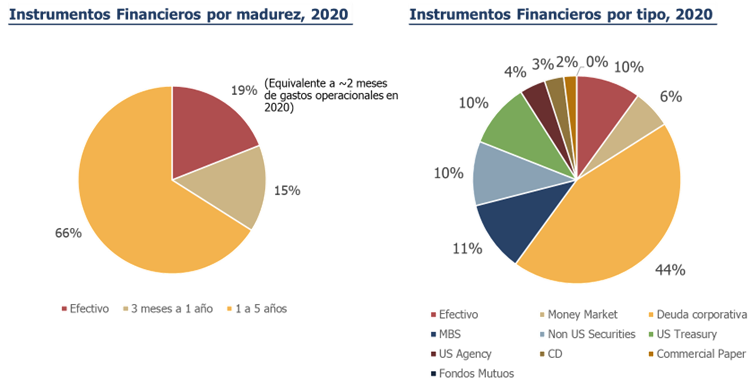

So, what does Braeburn’s investment portfolio look like? While it’s difficult to know for sure, in 2020, the portfolio looked like this:

The portfolio is primarily concentrated in corporate bonds, with the remainder evenly distributed among mortgage-backed securities, U.S. Treasury bonds, other government bonds, and money market funds. Note the duration of the instruments—66% have a maturity of between 1 and 5 years. To invest such a large amount of money for such a long period while adhering to the principle of capital preservation, it is necessary to employ the “key ingredient”: a robust short- and long-term cash projection that accurately identifies cash needs and establishes a reasonable cushion for contingencies.

Since 2017, the company has stated that it aims to maintain a neutral cash flow and has begun to reduce its cash holdings through a share buyback program.

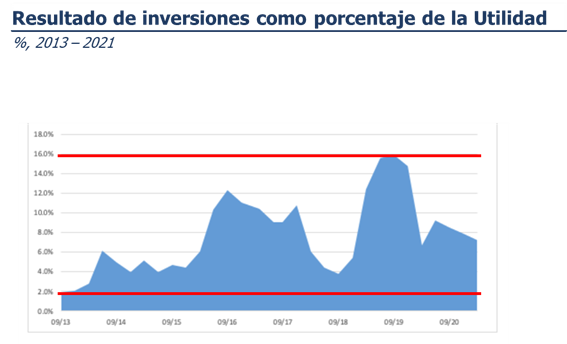

Apple’s conservative cash management strategy, though on an infinitely larger scale, aligns with what we have observed in companies in Chile and is similar to the experience of mutual insurance companies and some trade associations that accumulate cash and face investment restrictions. All of them follow a cautious investment policy that seeks to preserve capital without aiming for returns above the market and strives to match cash needs with the duration of instruments to maximize returns. While one might think this strategy has generated little return for Apple, the truth is that since 2013, it has accounted for between 2.5% and 16% of the company’s net profit. Not bad for conservative cash management, wouldn’t you agree?